Passwords are bad, and our whole industry is trying to move away from these simple strings granting access to our systems. But change is slow, and adopting newer standards is difficult, even if passwords are deeply problematic. Now, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) is updating the core standard for authentication – and it adopts the “new school” of password policies.

NIST is the federal agency providing technological standards for government bodies and commercial entities in the US. While NIST standards are only mandatory for government agencies, it is widely considered to be one of the gold standards in this space, setting a shared cybersecurity baseline for a wide variety of organizations. Among other standards, NIST develops and maintains comprehensive guidelines for cybersecurity. Recently, it published the draft proposal for Digital Identity Guidelines or “NIST SP 800-63.”

NIST reviews its recommendations at regular intervals – the 800-63 was last updated in 2016-2017. Back then, the agency made headlines by downgrading the security level that SMS-based 2FA provides, asserting that this second channel is not secure enough for this kind of use. Now, the agency has published the second draft for the fourth revision of the standard, 800-63-4. This draft now enters a new round of consultation and should get its final published form soon.

What’s new?

The 800-63 collection of standards sets guidelines for securing digital identities. The main standard is titled Digital Identity Guidelines, with additional publications focusing on “Enrollment and Identity Proofing,” “Authentication and Lifecycle Management,” and “Federation and Assertions.”

Probably the biggest practical news involves the rethinking of password policies, with NIST finally moving away from the traditional approach to password lifecycles, mandatory resetting and required characters – all very familiar to sysadmins worldwide. NIST is now updating the standard to eliminate mandatory password changes (absent evidence of compromise) and to eliminate composition rules for passwords. Instead, NIST guidelines set a new baseline of not allowing expiring passwords, and explicitly forbidding composition rules altogether.

The proposed new guidelines now state that:

- Verifiers and CSPs SHALL NOT impose other composition rules (e.g., requiring mixtures of different character types) for passwords and

- Verifiers and CSPs SHALL NOT require users to change passwords periodically. However, verifiers SHALL force a change if there is evidence of compromise of the authenticator.

Similarly, there are now new requirements around password length:

- Verifiers and CSPs SHALL require passwords to be a minimum of eight characters in length and SHOULD require passwords to be a minimum of 15 characters in length.

- Verifiers and CSPs SHOULD permit a maximum password length of at least 64 characters.

- Verifiers and CSPs SHOULD accept all printing ASCII [RFC20] characters and the space character in passwords.

- Verifiers and CSPs SHOULD accept Unicode [ISO/ISC 10646] characters in passwords. Each Unicode code point SHALL be counted as a single character when evaluating password length.

- Verifiers SHALL verify the entire submitted password (i.e., not truncate it).

Note: “Shall” and “shall not” represent requirements, while “should” and “should not” are strong recommendations. While not in this section, “may” means permission, and “can” represents an optional function. NIST also decided to move away from the term “memorized secret,” and uses the term “password” across the standard. Finally.

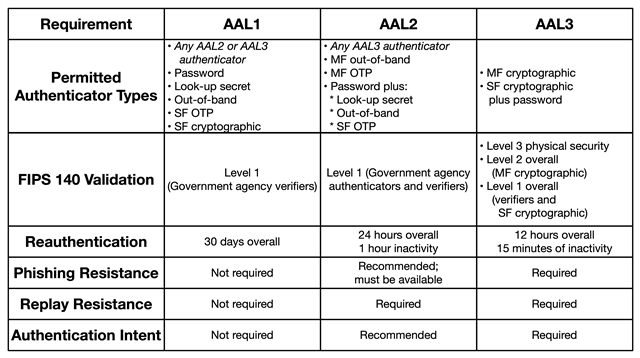

Of course, NIST doesn’t say we all should have a simple eight-character password protecting our accounts. The recommendation is 15 characters in length, and, ideally, passwords are to be combined with other authentication factors described in the standard – and anything but the lowest security level (AAL2 and AAL3) mandate another factor alongside passwords. Notably, the section on biometric factors didn’t change much: NIST still considers biometrics a probabilistic factor (and not deterministic like the others) and requires additional factors alongside it.

The updated NIST guidelines follow the pioneering work by Microsoft and others in the industry. The software company offered their Password Guidance in 2016, based on attacks against Microsoft’s identity platforms (Azure Active Directory, Active Directory and hundreds of millions of Microsoft accounts). The research-based recommendations caused quite a stir in IT admin circles, as they explicitly advocated against mandatory periodic password resets and instead focused on banning common passwords, education on password re-use and enforcing MFA. Eight years later, NIST is updating their set of recommendations, broadly matching that of Microsoft.

The main argument against composition rules and expiration is that they don’t make us safer. Research shows that these rules lead to frustration, and users eventually revert to simpler, more memorable and fundamentally less safe passwords and password policies. The modern, cutting-edge approach to authentication is to sideline the passwords altogether and use Advanced Authentication wherever possible.

As a sidenote, it looks like NIST is done with experimenting. In 2016, the organization decided to open the draft for feedback on GitHub as well, where it gathered more than 1500 issues (pieces of feedback). This time, there’s no sign of a GitHub repository, so feedback is available through the regular, somewhat bureaucratic channels available at the website of the draft. For practicing professionals, the whole document is a recommended read, as it lays out the best practices across all the covered segments.

Sadly, the NIST document is only one of the potential binding standards for large organizations, and some of the standards are still lagging behind on password policies. For example, PCI DSS (section 8.6.3) still requires mandatory periodic password changes and mandates construction rules.